Quantum Dice and the Delayed-Choice Quantum Eraser

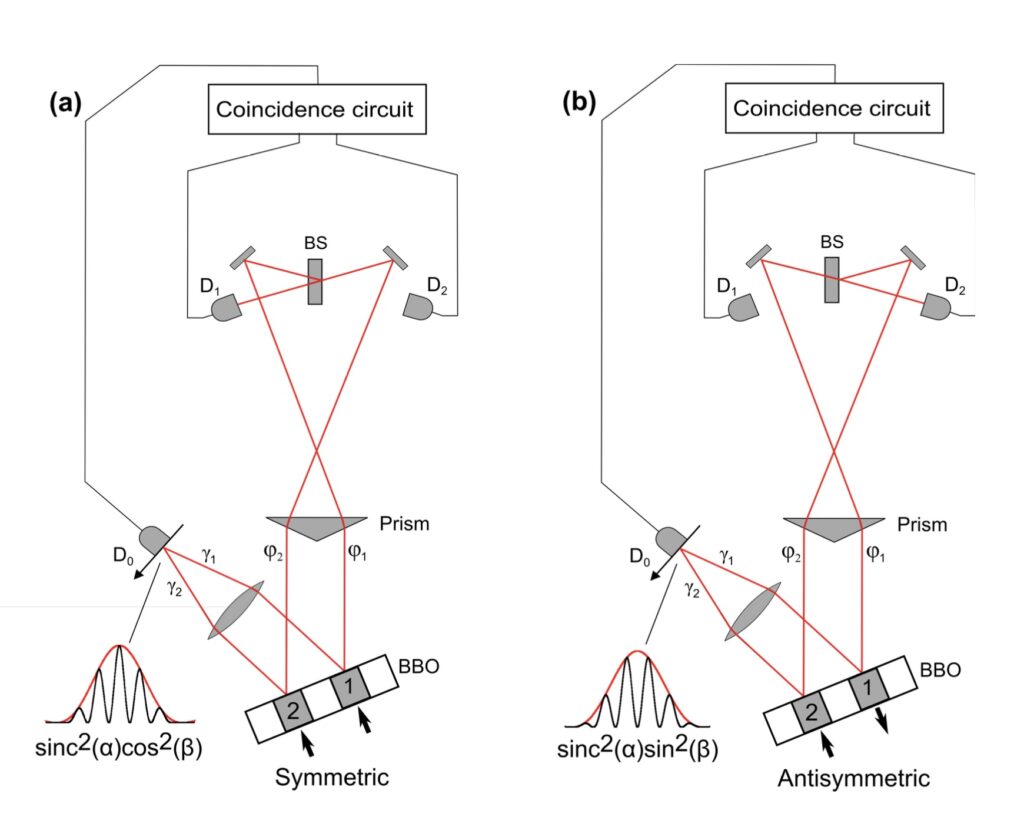

In my recent paper “Rolling the Dice on the Delayed-Choice Quantum Eraser,” I introduce a new interpretation of this famous experiment by equating its results to the random outcomes of a pair of entangled quantum dice. In this followup paper, I develop the interpretation further by using it to plot out the complete theoretical waveforms for all four joint-detection scenarios in the experiment.

Not only do the theoretical results closely mirror the symmetric and antisymmetric joint detections reported in the original paper by Kim et al., they also reveal an inconsistency with their data. Their reported single-slit joint-detection rates are too high to be part of the same data set that produced their double-slit joint-detection rates. One can only speculate on the cause, because the authors do not address this discrepancy in their paper.

The mathematical metaphor of entangled quantum dice offers a powerful and intuitive strategy for interpreting the utter randomness of the delayed-choice quantum eraser. By interpreting the experiment’s results as the random outcomes of a pair of entangled quantum dice, one can replicate the actual data with remarkable precision—and without violating the normal sequence of cause and effect. In so doing, this interpretation thoroughly refutes those upside-down “retrocausal” interpretations in which the present somehow affects the past.

To download a PDF of my latest analysis of the delayed-choice quantum eraser, click here or on the abstract page above.

To download a PDF of my previous paper, which introduces the entangled-quantum-dice interpretation, click here: “Rolling the Dice on the Delayed-Choice Quantum Eraser.”

To download a PDF of my backgrounder on this experiment, click here: “Disentangling the Delayed-Choice Quantum Eraser.”